When you think of vanilla or strawberry ice cream, the last thing you’d imagine is beavers. Yet for centuries, a little-known substance called castoreum—a secretion from a beaver’s castor sacs—has quietly made its way into food, fragrance, and even medicine. While it sounds shocking, castoreum has a surprisingly long history of safe use, though you’re unlikely to find it in your cone today. Why? Because despite its strange origin, it’s rare, expensive, and mostly used in niche products. Let’s peel back the mystery of this curious ingredient and see how it shaped food culture.

What Exactly Is Castoreum?

Castoreum is a secretion produced by beavers from glands near their tails. Mixed with urine, they use it in the wild to mark territory and identify family members. To humans, though, castoreum has been prized for its musky, vanilla-like scent and flavor. It has appeared in:

- Food flavorings like vanilla and strawberry syrups.

- Fragrances and soaps, where its sweet aroma enhanced perfumes and personal care products.

- Medicinal remedies, dating back centuries, where it was thought to treat fevers, stomach ailments, and even mental conditions.

The surprising part? For much of history, people consumed it without hesitation, and regulatory agencies like the FDA have deemed it safe.

Video: Scent Notes: Castoreum

Why You Won’t See “Castoreum” on Labels

Here’s where things get tricky. Even if castoreum was used in a flavoring, you wouldn’t see the word on your ice cream carton. Instead, it would fall under the broad term “natural flavorings.” This labeling makes it nearly impossible for the average shopper to know what they’re consuming.

Still, food companies rarely use it today, for two key reasons:

- Cost – Harvesting castoreum is expensive. Unlike vanilla orchids, you can’t cultivate fields of beavers.

- Certifications – Using castoreum disqualifies products from being labeled kosher, limiting their market.

Flavor chemist Gary Reineccius explained it best: “It’s not like you can grow fields of beavers to harvest. There aren’t very many of them. So it ends up being a very expensive product—and not very popular with food companies.”

Where You Might Actually Find Castoreum Today

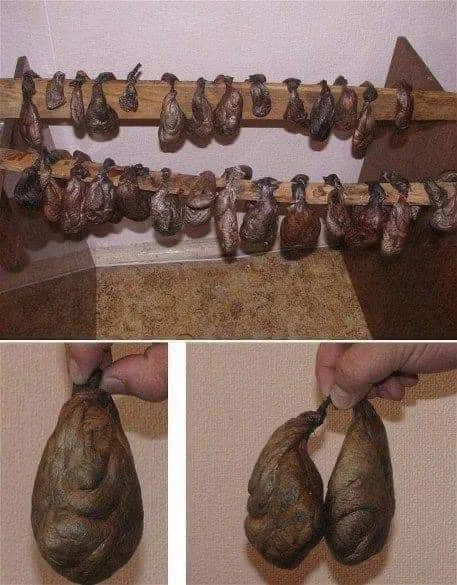

While mainstream food companies avoid it, castoreum still pops up in specialized products. In Sweden, for example, a liquor called bäversnaps proudly advertises its castoreum content. Here, its rarity and unusual origin are considered a selling point. The production process involves drying and grinding beaver castor sacs, then extracting flavor compounds with alcohol—similar to how vanilla extract is produced.

In modern perfumery, castoreum is valued as a rich, leathery base note, giving depth to high-end fragrances. And in traditional medicine, it once enhanced cigarettes with a sweet aroma while also being used in remedies for headaches and inflammation thanks to its natural salicylic acid content—the same active compound found in aspirin.

Beavers and the Fur Trade Connection

The popularity of castoreum rose during the fur trade era, when beavers were already being hunted for pelts. Unfortunately, this demand nearly drove them to extinction—first in Europe during the 16th century and later in North America in the 19th century. While beaver populations have since recovered thanks to conservation, the exploitation of castoreum is part of that complicated legacy.

How Beavers Use Castoreum in the Wild

Video: Why is there castoreum in your food products en what is it?!

For beavers, this substance is vital. They use it to:

- Mark Territory – Beavers are family-centered, and males typically do the marking.

- Identify Family Members – Each beaver’s castoreum has a unique scent signature.

- Protect Fur and Tails – The secretion helps waterproof their dense coats, giving them an advantage in aquatic environments.

So while humans found unusual uses for it, castoreum plays a natural role in beaver survival.

Is It in Your Ice Cream Today?

The good news: you don’t need to panic. Food companies rarely—if ever—use castoreum now. Vanilla and strawberry flavors are easy to recreate with plant-based compounds, making castoreum unnecessary. Chemists can mimic familiar flavors using just a few ingredients, and it’s far cheaper than sourcing from animals.

As Michelle Francl, a chemist at Bryn Mawr College, noted: “There’s no chance that beaver excretion of any kind is secretly in foods because of the high costs.” In other words, your vanilla latte is safe.

The Bigger Picture: What Castoreum Teaches Us About “Natural Flavorings”

The castoreum story highlights a larger point: food labels can be vague. “Natural flavorings” can cover hundreds of compounds, some plant-based, others animal-derived. While castoreum is mostly historical curiosity now, its existence underlines how little transparency consumers have when reading labels.

It also reminds us that the line between “natural” and “unnatural” isn’t always obvious. What sounds unappetizing (like beaver gland secretions) might actually be harmless—or even historically valuable. Meanwhile, what seems ordinary (like processed flavorings) may be synthetic but completely safe.

Conclusion: Strange but Safe, and Almost Gone

Castoreum’s journey from beaver sac to ice cream cone is one of the strangest chapters in food history. Once prized for its sweet, vanilla-like scent, it is now largely abandoned because of cost, ethics, and practicality. While it may occasionally appear in niche liquors or perfumes, the average consumer is unlikely to encounter it today.

Still, the story of castoreum is more than a curiosity—it’s a reminder of how human creativity stretches to surprising places, how industry choices shape what we eat, and how even the strangest ingredients can leave their mark on culture.

So the next time you enjoy vanilla ice cream, rest easy. You’re not tasting beaver secretions. But you are tasting a slice of history that shows just how inventive—and occasionally bizarre—our food traditions can be.