Most of us remember learning about Pavlov’s drooling dogs in school. But few know the tragic story of Little Albert—a 9-month-old baby boy who unwittingly became the star of one of the most unethical experiments in psychological history. The goal? To prove that fear could be conditioned in a human just like it could be in a dog.

The reality? It left a terrified child and a legacy of broken trust that still haunts the world of science today.

The Roots of Behaviorism: Conditioning and Control

Let’s rewind a bit. In the late 1890s, Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, discovered classical conditioning—the idea that animals (and people) could be trained to associate one thing with another. Pavlov rang a bell every time he fed his dogs. Eventually, just the sound of the bell made them salivate.

Fast forward to 1920. Inspired by Pavlov’s success, American psychologist John B. Watson, often dubbed the “father of behaviorism,” decided to take this theory further. He wanted to condition fear—a raw, primal emotion—into a human child. That’s where Little Albert came in.

Video: The Little Albert Experiment

The Experiment: From Curiosity to Cruelty

Albert, whose real name was unknown for decades, was chosen for his “emotional stability.” Watson and his assistant, Rosalie Rayner, described him as a calm, happy baby. They saw him as the perfect blank slate.

At first, Albert was shown soft, furry animals like a white rat, a rabbit, and even a monkey. He reached for them without hesitation. No fear. Just pure, innocent curiosity.

But then came the twist.

Every time Albert touched the white rat, Watson struck a metal bar behind him with a hammer—creating a terrifying, sudden noise. Albert flinched. He cried. Over repeated trials, he began to associate the once-adorable rat with that awful sound.

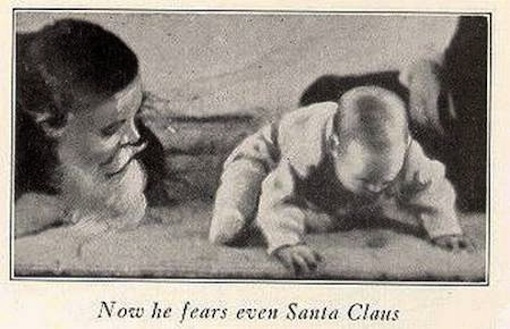

Soon, Albert wasn’t just scared of the rat—he was terrified of anything furry or white. Dogs. Rabbits. A Santa Claus mask. Even his mother’s wool coat. Fear had been planted, and it spread like wildfire.

Consent? None. Compassion? Missing.

Let’s be clear: Albert was a baby. He had no idea what was happening to him. He couldn’t give consent. And the worst part? Watson kept his mother in the dark about the true nature of the experiment.

When she eventually found out, she pulled him from the study immediately. Watson promised to “decondition” the fear they had created, but he never followed through. Albert left the experiment just as scared as he was during its peak—and no effort was made to help him recover.

Unmasking Little Albert: A Decades-Long Mystery

This is in loving remembrance of Douglas Merritte who was my little Albert in the "Little Albert Experiment".Thank you for your greatness! pic.twitter.com/FvEBFghJhr

— John B. Watson (@John_B_Watsonnn) September 21, 2016

For nearly 90 years, no one knew what happened to Little Albert. Watson never wrote down his real name, and his identity faded into obscurity. That is, until a team of determined psychologists launched an investigation in 2009.

After digging through hospital records, studying photographs, and comparing facial features, researchers concluded that Little Albert was most likely Douglas Merritte, the son of a wet nurse at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The discovery brought with it another layer of heartbreak: Douglas died at the age of six from hydrocephalus, a condition where fluid accumulates in the brain. Even more disturbing? Records suggest he may have already been showing signs of neurological issues before the experiment began.

A Study Built on a Flawed—and Possibly Exploitative—Foundation

Experts now believe Watson may have manipulated the facts. Douglas didn’t appear emotionally stable or “normal” as Watson claimed. In fact, his behavior in the surviving footage suggests just the opposite.

There are no smiles. No signs of social engagement. No attempt to seek comfort from the adults around him when frightened—something infants naturally do. Instead, Douglas sits silently, disconnected and visibly distressed.

Many now argue that the Little Albert experiment wasn’t just unethical—it was based on a lie.

Ethical Reckoning: What We Learned (and What We Didn’t)\

Video: The Little Albert Experiment Was Cruel

Today, the Little Albert study is taught in nearly every introductory psychology class—but not as a shining example of scientific discovery. Instead, it serves as a cautionary tale.

It reminds us of what happens when the pursuit of knowledge tramples over basic human dignity. Watson may have been hailed as a pioneer, but his failure to protect his subject—and his blatant disregard for ethics—left a stain on the field of psychology.

Psychologist Dr. Alan Fridlund didn’t mince words when he called the study a case of “medical misogyny,” exploitation of the disabled, and possible scientific fraud. And sadly, there’s no happy ending. Douglas Merritte wasn’t just a data point in a groundbreaking theory—he was a child. One who suffered. One who was forgotten.

The Human Cost of Curiosity Without Conscience

Science is meant to enlighten, not destroy. The tragedy of Little Albert lies in how easily a child’s pain was brushed aside in the name of discovery. There were no safeguards. No second thoughts. Just a theory—and a baby caught in the crossfire.

In the end, Little Albert’s short, painful life serves as a somber reminder: Just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should.

Conclusion: Remembering Douglas, Not Just “Albert”

Behind every experiment is a human being. And in this case, behind the cold, clinical label of “Little Albert” was Douglas Merritte—a little boy with a big head, a quiet spirit, and a tragic fate.

He wasn’t a theory. He wasn’t a case study. He was a child.

Let’s not forget that.